On May 3, 1978, President Jimmy Carter gave a speech on solar energy at the Solar Energy Research Institute — now the National Renewable Energy Laboratory — in Golden, Colorado. “Nobody can embargo sunlight,” he said, a reference to the geopolitical oil crisis then gripping the nation. “No cartel controls the Sun. It will not pollute the air; it will not poison our waters. It’s free from stench and smog.”

Carter vowed to spend hundreds of millions of federal dollars on solar research and development and predicted that solar would provide half of the nation’s power by 2020.

“No cartel controls the Sun. It will not pollute the air; it will not poison our waters. It’s free from stench and smog.”

Carter’s environmental accomplishments have been widely hailed since his death, at the age of 100, during the waning days of 2024. He has been called a “conservation legend” for designating 39 new National Park System units, including parks and monuments, national recreation areas and historical parks and sites, ranging from Alaska’s Wrangell-St. Elias, the nation’s largest park, to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. He signed the law creating the Superfund program and has been eulogized as a “river hero” for promising to nix 19 federal water projects and dams, including six in the West, due to their cost and environmental impacts. He urged Americans to dial down their thermostats, shut off the lights and take public transit — even had solar panels installed atop the White House. (His successor, Ronald Reagon, promptly had them removed.) Carter’s accomplishments were significant, and yet environmental, climate and public lands legacy is far more complicated — and contradictory — than the public eulogies would suggest.

James Earl Carter was elected president during an especially tumultuous time in American history. The Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal were still fresh on Americans’ minds, and militant leftist groups were waging their own battle against the establishment. Congress had just passed the Federal Land Management Policy Act, which mandated “multiple use” for public lands and thereby helped seed the Sagebrush Rebellion. But all that was eclipsed by the energy crisis and the sudden scarcity of the fossil fuels that had always powered the nation.

In the early 1970s, the U.S. imported about 6 million barrels of oil per day — more than one-third of its total consumption — to fuel its citizens’ beloved cars, power plants, factories and farm equipment. So, in 1973, when the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC, halted oil exports to America and its allies in retaliation for backing Israel in the Yom Kippur War, it hurt — a lot. Global crude prices tripled, and motorists lined up at gas stations, at times finding only empty pumps. The 1979 Iranian Revolution caused the price of crude and of gasoline to climb even higher.

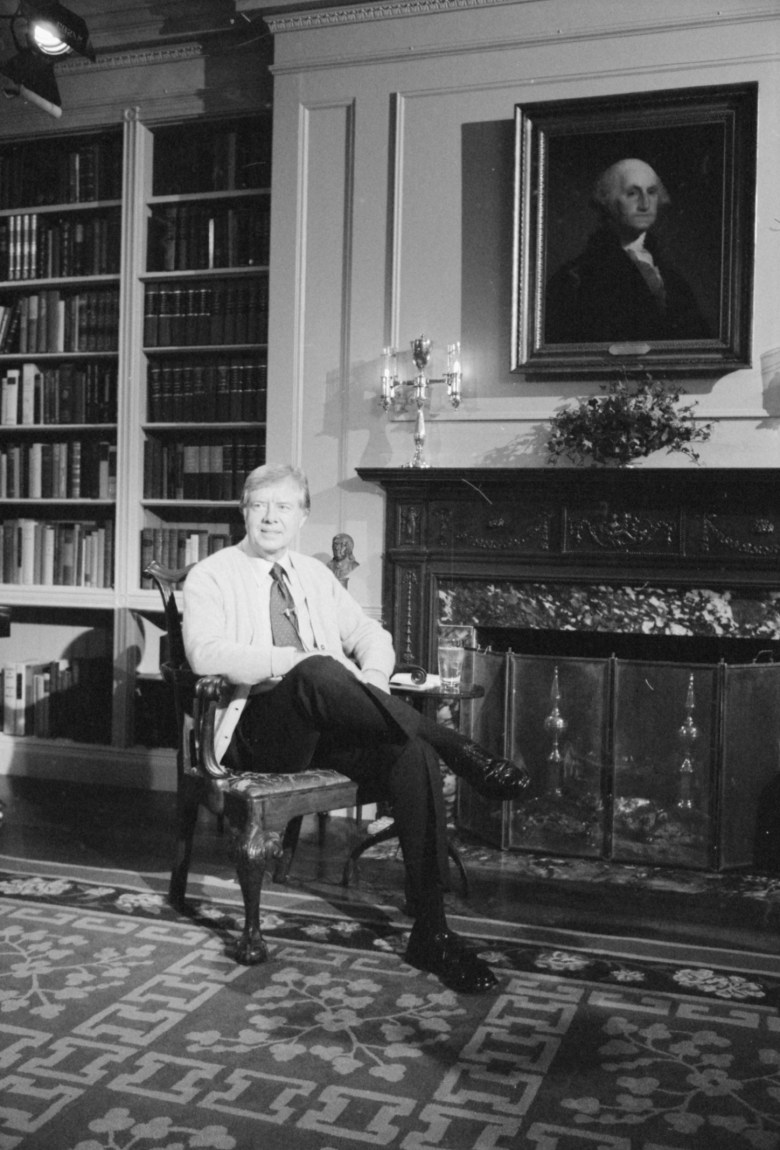

Thus was born the quixotic quest for “energy independence.” In February 1977, just weeks after being inaugurated, Carter donned a beige cashmere cardigan and, from a comfortable perch in front of the White House fireplace, delivered the first of many televised speeches laying out his plans to wean the nation from foreign oil. He touted solar and wind and emphasized the need to “conserve the fuels that are scarcest” by turning off the lights and driving the speed limit. But his answer to the energy scarcity question was not exactly what we would call “climate friendly” today. “We need,” he declared, “to shift to plentiful coal.”

Yes, conservationist Carter still lusted after coal, and his ardor continued to grow as his term — and the energy crisis — wore on. In 1978, at his urging, Congress banned new power plants from using natural gas or oil, in order to reduce the nation’s reliance on importing those fuels, a move that automatically increased U.S. coal consumption. Carter wasn’t just interested in burning coal to generate electricity, but also in “gasifying” it to create a diesel-like fuel for planes, trains and automobiles. Near the end of his time in office, Carter managed to secure tens of billions of dollars in federal subsidies for one of his pet programs — producing these “synfuels” from coal, oil shales and tar sands — calling it “the most massive peacetime commitment of funds and resources in our nation’s history to develop America’s own alternative sources of fuel — from coal, from oil shale, from plant products for gasohol, from unconventional gas, from the sun.”

And the largest, most accessible deposits of coal and oil shale lay within the public lands of the Western U.S. On the one hand, the Carter administration vowed the end of “the days when economic interests exercised control over decisions on the public domain,” promising that this new approach would “exercise our stewardship of public lands and natural resources in a manner that will make the ‘three Rs’ — rape, ruin and run — a thing of the past.” On the other, Carter’s policies and rhetoric helped spark a fair bit of raping, ruining and eventual running of their own in the form of the Powder River Basin coal-mining boom, an oil- and gas-drilling frenzy and a surge of destructive and water- and energy-intensive oil shale projects on Colorado’s Western Slope — all on federal lands.

“Westerners knew even that the price of energy independence might be the conversion of their world into a national sacrifice area,” wrote former Colorado Gov. Richard Lamm in his 1982 book, The Angry West. Lamm lamented Carter’s contradictory policies in other realms, as well. Carter hoped to site MX nuclear missile launching facilities across the Great Basin and Northern Plains, and he called for more logging as a way to ease rising housing costs even as he worked to establish more wilderness and roadless areas. Nearly all the water projects and dams on Carter’s “hit list” — including the Dolores Project and the Central Arizona Project — were ultimately built at the expense of the rivers they harnessed.

Lamm’s frustration was understandable. Looking back from half a century, however, we can see that Carter’s merits — both during and after his time in office — transcended his faults. He brought intelligence, integrity, humility, compassion, selflessness and duty to the presidency during a critical moment in the nation’s history, and his desire to preserve our spectacular landscapes and public lands was genuine, as his record of land protection shows. But the political realities of the era pushed him into the still widely held belief that we can drill, mine or solar-panel our way out of our energy woes. Yet despite all the oil and gas activity he encouraged, production failed to increase significantly, and ultimately the synfuels projects imploded in catastrophic fashion.

In the end, Carter’s sincere desire to conserve was his most effective initiative.

In the end, Carter’s sincere desire to conserve was his most effective initiative. U.S. oil imports began falling dramatically in 1980, not because the U.S. was producing more, but because its citizens were guzzling far less gasoline, thanks in large part to relatively ambitious car fuel economy standards. It’s a lesson we need to remember in our current fight against climate change: Instead of always obsessing about building more — more wind turbines and solar panels and nuclear plants — perhaps we need to just use a little less. Carter put it best in his 1979 “crisis of confidence” speech, an almost homiletic lamentation of America’s worship of “self-indulgence and consumption.” “We often think of conservation only in terms of sacrifice,” he said. “In fact, it is the most painless and immediate ways of rebuilding our nation’s strength. Every gallon of oil each one of us saves is a new form of production. It gives us more freedom, more confidence, that much more control over our own lives.”