“Grandson, I’m going to ask you questions about this rock,” said Charles Sams I, pulling a stone from the clear waters of Iskuulpa Creek where it wound between grassy lomatium-covered hills and the shaded curves of pine-stippled ones. He sat on the riverbank with his young grandson, pondering the stone in his hand, which mid-Columbia River tributaries had tumbled smooth on its journey through the high desert.

“How do you think this rock was formed?” the elder Sams inquired patiently, meting out his words. “How does a rock move in the water?” He asked how it might have rolled down from the mountain and who could have swum past or stepped on it, noting a periwinkle attached to its side. “Do you think the rock has been in a dry place before?”

Charles’ grandson, Charles “Chuck” Sams III, listened attentively. Through these experiences, Sams III recalled, “I was learning math, I was learning science, I was learning history.” An Indian education, he explained, is different than a Western one. A Western education starts with a general understanding of the world, encompassing math, science, literature, then becomes hyper-specialized in higher education. “The Native way of understanding is, I’m going to give you something very specific, and then I’m going to teach you the broader world so that you understand where your place is in that broader world, and the connections you must have,” he said.

The elder Sams had experienced both types of education. As a child, he attended a Catholic boarding school on the Umatilla Indian Reservation. When he became a teenager in the late 1930s, his parents took him into town, bought him some new clothes, and sent him over 200 miles west by train to Chemawa Indian School in Salem. Sams remembers his grandfather saying, “I was one of those that was sent by my parents. I wasn’t taken by an Indian agent.” Nevertheless, Sams noted, his grandfather saw firsthand the destruction of his language and witnessed the beatings of children there.

“The Native way of understanding is, I’m going to give you something very specific, and then I’m going to teach you the broader world so that you understand where your place is in that broader world, and the connections you must have.”

Sams’ relatives survived such schools not only in Oregon, but also in Montana, Arizona, New Mexico, California and Minnesota, as well as the notorious Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania. Indian boarding schools dismantled millennia of Indigenous education and understanding about how to interact with the world, he said, forcing conformity to the dominant culture instead. “It definitely was a cultural genocide.” His parents and grandparents occasionally talked about the schools, but were more concerned with ensuring the family, not the government, charted the next generation’s education. Sams, his siblings and his cousins went to public schools instead.

After graduating high school in Pendleton, Sams served four years as a Navy intelligence officer with top-secret clearance. He received an undergrad in business administration from Concordia University in Portland and a master’s in Indian law from the University of Oklahoma. It was a formal education in the American system, but he said he considers his grandparents’ teachings a formal education, too.

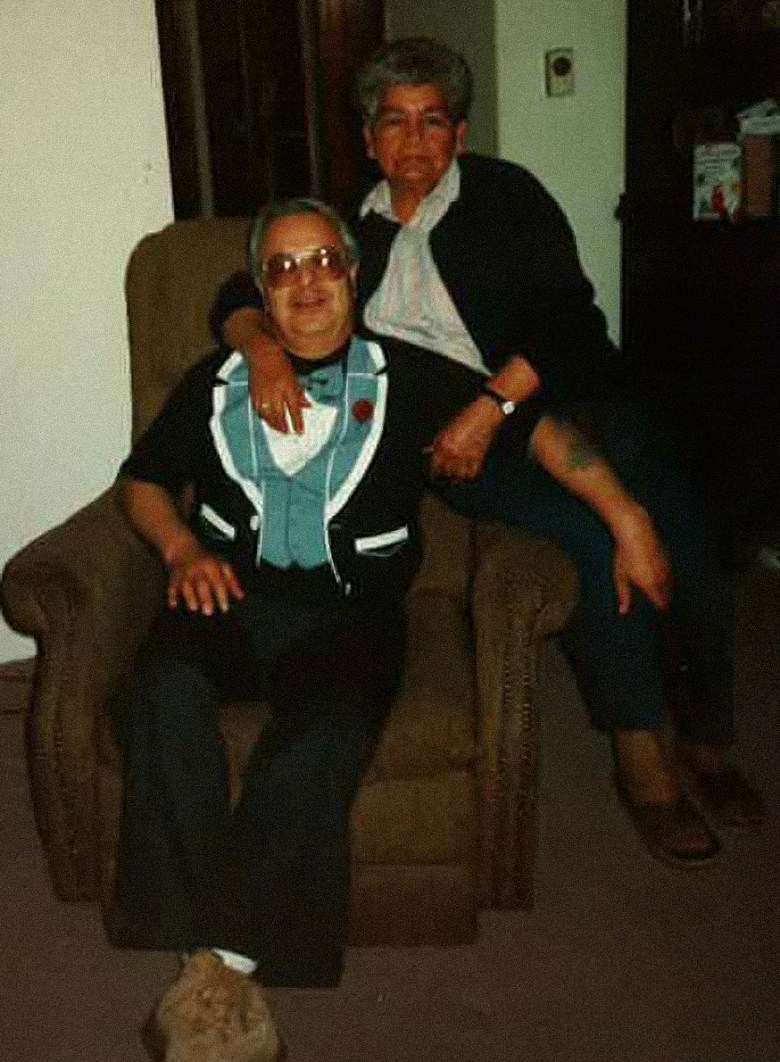

Charles and Ruby Sams on the Umatilla Indian Reservation, in the winter of 1944 (right). Courtesy of Charles “Chuck” Sams III

WHEN THE ELDER SAMS was a teenager, he decided to escape from Chemawa and he hatched a plan to spring some of the younger boys along with him.

“Because his older brother had worked on Union Pacific, he was able to smuggle them onto trains, bring them back to the Umatilla Indian Reservation and take them up a place called Iskuulpa Creek,” his grandson explained. There, on the banks of the same creek where he would later teach his grandson, the elder Sams killed a deer, told the younger boys to eat on it for a few days and hide from the Indian agent so they could go back to their parents. Then he turned himself in — “knowing full well that he’d probably get beat and sent back to Chemawa,” said Sams. The boys were grateful: “Those men, some of them are still alive today and talk about when my grandfather did that for them.”

Back at Chemawa, a new student appeared — Ruby Whitright, a Yankton Sioux tween the Bureau of Indian Affairs had kidnapped in retaliation for her father’s community activism over a government dam-building project in Wolf Point, Montana.

At Chemawa, Whitright had three square meals a day, a warm place to sleep, and she was learning new things. While she missed her home, the Depression-era conditions on the reservation weren’t exactly luxurious. Besides, it was at Chemawa where she met Sams’ grandfather — the grandfather of her future grandchildren.

IN DECEMBER 2021, Sams III stood with Interior Secretary Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) before the marble columns of Washington D.C.’s larger-than-life monument to Indian killer Abraham Lincoln. Haaland guided Sams through his oath of office as he became the first-ever Indigenous director of the National Park Service. “Secretary Haaland told me: We must be fierce in our storytelling,” he said, and to go find those stories yet untold.

“Secretary Haaland told me: We must be fierce in our storytelling.”

Sams, whose last day leading the agency was Jan. 20, focused largely on education during his tenure. “We have the largest outside classrooms in the United States,” he told HCN in 2022. As Haaland traveled the country with Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Brian Newland (citizen of the Bay Mills Indian Community) listening to the stories of boarding school survivors for her historic report on the subject, Sams made it his mission to educate park visitors about Chinese immigrant and Chinese-American contributions to Yosemite, the tiny handprints of enslaved Black children in the walls of Fort Pulaski, and the other side of the Whitman Mission “massacre” — his own tribal history — which explains Whitman’s killing from an Indigenous perspective. “We’ve been raising those voices, and that’s been very exciting to me,” he said.

When the Biden administration sought to designate a new national monument, Sams collaborated with Haaland to bring boarding school stories into the park system. After the release of the federal Indian Boarding School Report, they considered which place tribal communities might recognize as seminal to boarding school injustices.

They visited the boarding schools in Phoenix and Santa Fe his mother had attended, Albuquerque and St. Paul, and looked at Chemawa as well. “We looked across the country,” Sams said. “But all of those off-reservation boarding schools really have a direct tie back to the Carlisle barracks.” After Haaland and Newland canvassed Indian Country for stories of boarding school horrors, Haaland wanted Sams to use the National Parks system to help tell those stories. So all three met with the Army and discussed Carlisle founder Captain Richard Henry Pratt’s famous directive to “kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Everyone agreed that Carlisle’s horrific past caused great cultural, social, and in many cases educational damages to Native people, Sams said.

On Dec. 9, 2024, President Joe Biden designated the Carlisle Indian Industrial School — a place synonymous in Indian Country with torture and suffering — as the newest national monument. “This addition to the national park system that recognizes the troubled history of U.S. and Tribal relations is among the giant steps taken in recent years to honor Tribal sovereignty and recognize the ongoing needs of Native communities, repair past damage and make progress toward healing,” Sams said in a press release at the time.

Education and storytelling were not Sams’ only focus as he helmed the Parks. In March 2022 Sams met with Congress and Native leaders to promote the expansion of co-management and co-stewardship between the federal government and the tribal nations that call the parks home. That fall, Interior released its first Annual Tribal Co-Stewardship Report; by the end of Sams’ tenure, the number of parks co-stewarded by tribal nations increased from about 80 to 109, with another 56 parks with co-stewardship activities outside of a formal agreement.

AFTER ATTENDING CHEMAWA, Ruby Whitright went to live among the elder Sams’ people, the Cayuse and Walla Walla. They raised their children and grandchildren there, in Umatilla country, near Iskuulpa Creek. While the couple wouldn’t live to see their grandson usher in Carlisle as a new national monument, Sams still carries their stories — including his grandpa’s words about the river rock. Today, he keeps that stone in his medicine pouch. He joked that it raises eyebrows with TSA agents when he travels for work. “I tell them it is a religious token of mine, and they’ve been very respectful.” While he values his Western education, he said, “the one I value more is the one that taught me a much broader aspect of what it means to be a human being among flora and fauna, among the land, the water and the air.”

Note: This story was updated to correct the number of parks co-stewarded by tribal nations at the end of Sams’ tenure.

We welcome reader letters. Email High Country News at editor@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor. See our letters to the editor policy.