Like the hardrock miners who flocked to Montana in the 19th century, cattle rancher Rick Jarrett looks to eke out a living and keep his family afloat in The Crazies (January 2025). But these days, money is not just buried deep underground, like the “Oro y Plata” that gave the state its motto; it surges from the mountains as wind. This narrative nonfiction book, by Wall Street Journal reporter Amy Gamerman, is a well-researched unspooling of a modern-day tale about land ownership, preposterous wealth and the legal scrum that ensued after two ranchers sought to lease their land to wind developers in Montana’s Crazy Mountains, near Big Timber.

Using detailed, vernacular sentences that hew closely to her characters’ perspectives, The Crazies unravels a NIMBY phenomenon that is happening across the West as the U.S. pushes to decarbonize, while landowners look to profit from a “new gold rush.”

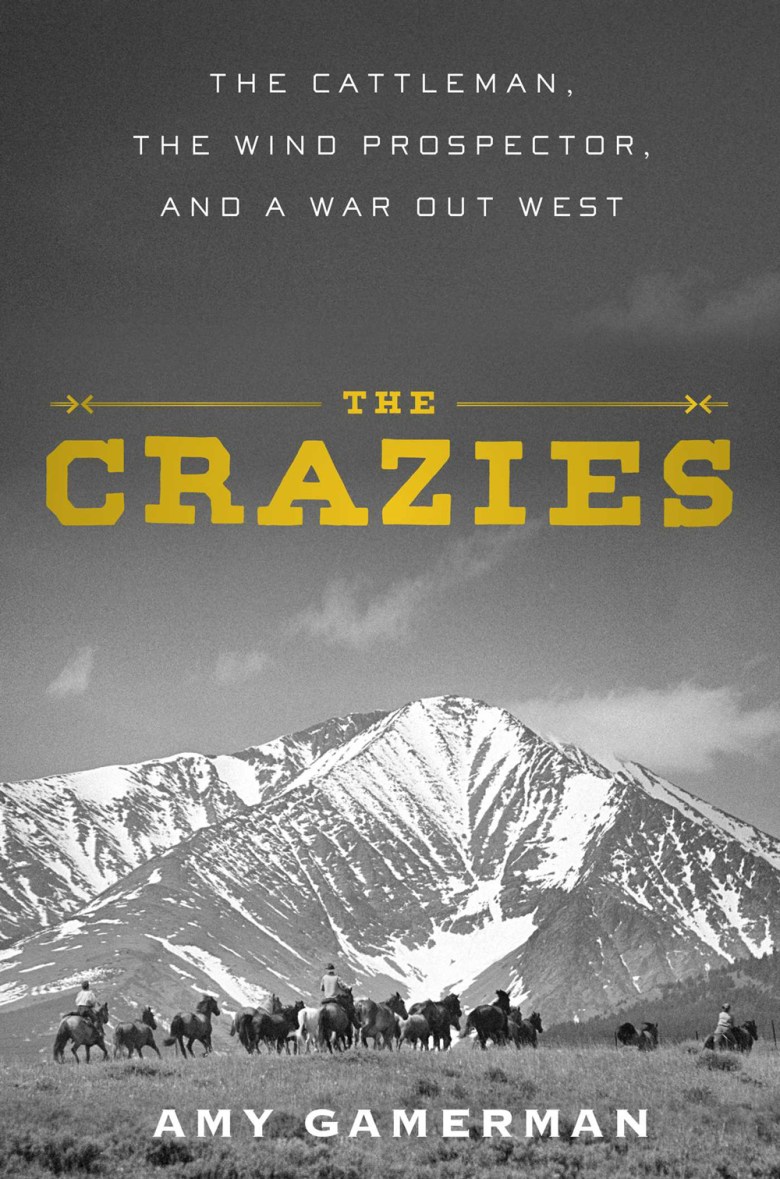

The Crazies: The Cattleman, the Wind Prospector, and a War Out West

Amy Gamerman, Simon & Schuster, 2025.

464 pages, hardcover: $26.99

But their wealthy neighbors generally don’t want industry sited anywhere near where they live, and Jarrett, who died in January 2023, happens to reside near some of the wealthiest: three billionaires and others with sizable fortunes who believe turbines will spoil their view or harm wildlife. They do everything they can to stymie the project, called Crazy Mountain Wind: They attend public hearings, file lawsuits, finance a false grassroots campaign against it and plant negative stories in the local press. Resistance also comes from local government: One of the commissioners on Montana’s public utility regulator insists that CO2 does not have a “negative impact” on the environment. At a meeting held hours after Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, another questions a utility’s assumption that future government regulations will shrink emissions to stave off climate change. Twelve hours before, he would have agreed. “But now the person who is the executive above those relevant agencies, you’re aware that he said that this isn’t real?”

ENVIRONMENTALISTS ARE CURIOUSLY absent from the book. When the rich neighbors try to involve a local nonprofit, it declines. The billionaires’ campaign to squelch the wind farm does not appear to be motivated by a conservationist ethos. Land exploitation is the source of one opponent’s wealth: He makes millions off fracking operations in a Colorado wilderness. Nor are the development’s proponents motivated by an urge to save the planet, a fact that testifies to the current state of green energy: It has become big business.

“Rick didn’t know if he believed in climate change, but he did believe in doing what he could to make money.”

“Rick didn’t know if he believed in climate change, but he did believe in doing what he could to make money,” Gamerman writes. Cattle ranching is grueling, replete with mounting debt and narrow profits. The national energy developer that eventually buys Crazy Mountain Wind, Pattern Energy, does what it can to make it happen: A company envoy in Big Timber holds community meetings, bids on livestock at the county fair and arranges a $100,000 donation to the local school. While monied interests oppose the project, there is much riding on its success, too.

Clean energy projects can get stuck in a vise, rendered nearly impossible to build when a web of contingencies runs up against delay tactics. Gamerman adeptly unfolds this case’s specifics: Litigation scares away investors, and unless a venture is built by the agreed-upon date, the public utility required to buy the electricity can blow up the contract — and along with it, the guaranteed tax credits and prices that make it worth investing in in the first place. Reforms aimed at encouraging renewables don’t do the trick, either: One Carter-era program has size caps in Montana that prevent proposals from making financial sense, while a more recent state initiative requires local ownership — a near impossibility given the capital needed to get a wind farm built.

Though the book doesn’t offer much macro analysis, in tracing Crazy Mountain Wind’s challenges, it dramatizes what has become a well-worn path for clean energy projects across the country. One-third of wind and solar projects proposed between 2016 and 2023 were derailed by community opposition, according to one survey. Estimates for the land needed to convert all power sources to clean electricity range from the size of Arizona to that of Texas. The largest landowners, by a wide margin, are the most likely to oppose new projects, according to a recent Heatmap survey.

Woven into the narrative is the nearby Crow Nation’s history of land dispossession.

Woven into the narrative is the nearby Crow Nation’s history of land dispossession. Buried beneath layers of sandstone talus on a cliffside in the Crazies are the 12,500-year-old remains of a boy, laid to rest beneath unused tools and weapons. As the wind debacle unfolds, the Apsáalooke citizens of the Crow Nation push to retain access to the “cathedral” of their ancestral mountains, now in private hands. Calling attention to cultural traditional sites unsettles the property rights claims central to the wind farm’s viability. It also serves as a reminder of how the resources of the rich can shape the built environment, burdening poorer communities with more than their share of energy projects.

The project ultimately fails, felled by the wealthy neighbors’ litigation and a settlement agreement. As the next generation of Jarretts take over the ranch, Rick anxiously watches the Crazy Mountains’ declining snowpack, which is a threat to his family’s irrigation water. What The Crazies makes clear is how the pace at which these projects move clashes with the speed at which atmospheric carbon continues to increase. The saga of Crazy Mountain Wind — from the earliest feasibility studies and environmental reviews and permits to the struggle for financing and the litigation that follows — spans almost 20 years. Gamerman cites one study that found achieving net-zero by 2035 requires increasing wind capacity one-thousandfold. Which leads one of the study’s authors to a bigger question about the fate of wind farms across the country: “How many can you walk away from?”